The Graves on the Hillsides Still Speak: What Kaja Kallas Gets Wrong About Irish History

Ireland’s past is written in famine, exile, and resistance — not absence. When the EU's chief diplomat questions our experience of suffering, she reveals her historical amnesia

There’s a particular tone of voice you can easily recognise in certain political performers—the clipped, unearned certainty of people who know the lines but have never lived the scenes. You hear it often enough in Brussels, but it rang out like a cracked bell this week when Kaja Kallas, the EU’s newest foreign policy chief, decided to give Ireland a history lesson.

Addressing a debate on NATO and security, she turned her gaze west and declared that while her native Estonia had endured “atrocities, mass deportations, and cultural suppression” behind the Iron Curtain, Ireland had simply “built up its prosperity.” The implication was plain: the Irish don’t understand what real suffering looks like.

The EU has entrusted its foreign policy to someone who appears to be playing a grown-up’s game in a child’s shoes.

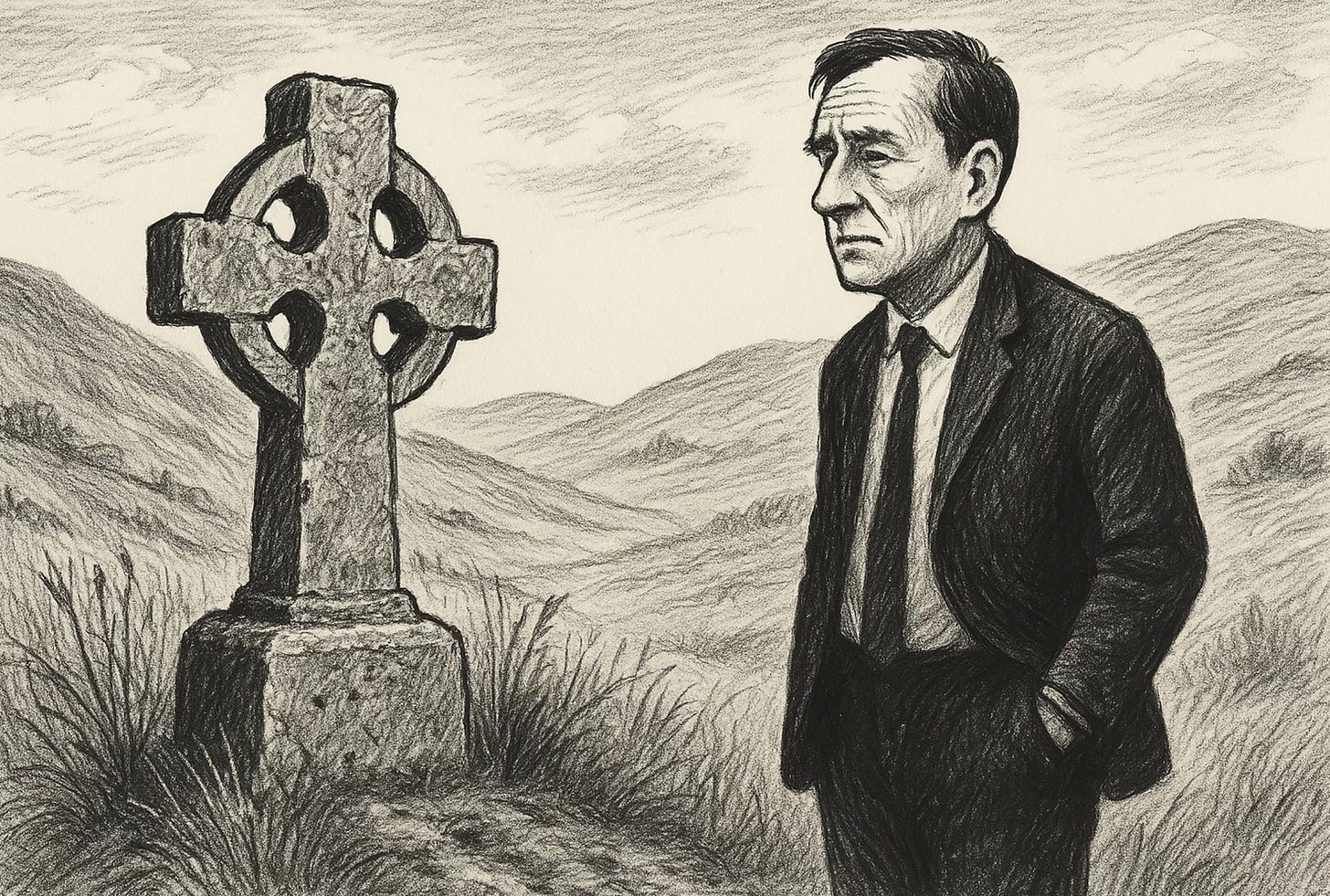

Because Ireland is, by any sober reckoning, one of the very few nations on earth whose population remains lower than it was in the 1840s. We had over eight million people before the famine hit. We’ve never come close to that figure since. Whole counties were practically emptied, not by warplanes or tanks, but by slow starvation and the forced emigration that followed. Families vanished across oceans and generations. Graves were dug in silence on hillsides that hadn’t known ploughs in years.

If that doesn’t qualify as atrocity, I’d like to know what does.

We didn’t have to wait for Stalin to see cultural suppression in action. We had a state that criminalised our language and mocked our music. We were ruled for centuries by a neighbour whose every policy, from plantation to partition, was designed to diminish us. And yet there she was — Kallas — explaining to us that we’ve somehow missed out on the harsh lessons of history.

But of course, this wasn’t really about Ireland. It was about her. This is a woman who has built her political brand on a posture of unyielding anti-Russian rhetoric, which would be easier to take seriously if it weren’t so obviously stitched together with threads of opportunism.

Kallas is often spoken of in the hushed tones Brussels reserves for its regional high-flyers. But peel back the glossy photos and recycled slogans, and you find something else entirely — the daughter of a senior Soviet official, a man who edited the Communist Party’s house newspaper in Estonia and spent nearly two decades climbing the ladder of power in the USSR, before quickly reinventing himself as a liberal under perestroika. Her Russian is fluent, her English falters. She grew up not in resistance to the Soviet machine, but comfortably within its walls.

That wouldn’t matter — people change, families change — if she didn’t now spend her political life proving just how changed she is. Her anti-Russian zeal is not just fervent, it’s performative. She has moved to help erase Russian-language schooling and media at home, even as a third of her country speaks it as their mother tongue. This is not strength. This is overcorrection. A need to prove that she is no longer her father’s daughter — or at least, that nobody will dare suggest it.

Her diplomacy abroad is no less selective. She refuses to even entertain dialogue with Moscow, painting any effort at negotiation as a form of surrender. And yet she stands beaming next to the petro-dictators of Central Asia, toasting “important partnerships” with regimes like Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan — governments that make the Kremlin look like a rotary club.

Earlier this year, her big diplomatic debut in Washington was unceremoniously cancelled. Marco Rubio wouldn’t even give her a handshake, let alone a photo-op. For a woman who has spent her career proving loyalty to NATO, it was a brutal reminder that obedience does not guarantee relevance.

But the most dangerous thing about Kallas isn’t her hypocrisy — it’s her naivety. She speaks of breaking Russia into “smaller pieces,” as if statecraft were a game of Risk. She seems blind to the idea that when you back a nuclear power into a corner, you may not like what comes out.

All of which would be bad enough if she were a foreign minister in Tallinn. But she now speaks on behalf of the entire European Union — 450 million people whose security and prosperity may depend on precisely the sort of diplomatic skill and strategic subtlety that she has shown no capacity to wield. Any fighter who confuses bravado with courage will soon find the canvas. Real fortitude lies in listening, in knowing when to lean back on the ropes and when to punch. But what Kallas offers instead is the perpetual wind-milling of a bantamweight who mistakes volume for power.

And that brings me back to Ireland — not as a special case, but as an example of what happens when you’re represented by people who know your name but not your history.

To pretend that Ireland somehow sat out the convulsions of the 20th century is to ignore the bombs in Belfast, the torment in Derry, the terror of the Black and Tans, the burning of Cork, the war waged in hedgerows and tenements, and the civil war that followed with all its betrayals and executions.

We didn’t avoid history. We were ransacked by it. And in many ways, we’re still living with it.

If Kaja Kallas wishes to keep lecturing on atrocities, she might first pay a visit to Connemara, count the famine graves, and ask how a nation still short of its pre-An Gorta Mór population knows nothing of loss. Until then, she’d do well to keep her history lessons — and her diplomacy — to herself.

Ireland the first colony of the English the model for the new form of empire the transplantation of economic imperatives (a developing British capitalism) the forcible colonial expropriation of the indigenous Irish people and settlement (Northern Ireland the Ulster plantations). A history Kallas and her EU centred elites recognise and approve in Israel today the expropriation of the Palestinians the appropriation of their land and economic transplantation becoming genocide. Even unto I would say the famine the deliberate starvation of Palestinians in Gaza the similarities are glaring. This must explain her flippancy her insensitivity to Ireland its history and the normalcy of her brutality and ignorance.

The sooner people like Kallas fade from relevance, the better.